It was the presence of disenchanted learners that started the Project-Based Learning (PBL) movement in the 1960s (Barrows, 1996; Neville, 2009). PBL allows students to move away from passively listening and simply repeating back what they heard. With PBL, students are asked to think about the relevance of the subject they are currently learning. They apply that understanding by working with peers in an environment that models professionalism and by focusing on what the end product will look like.

It was the presence of disenchanted learners that started the Project-Based Learning (PBL) movement in the 1960s (Barrows, 1996; Neville, 2009). PBL allows students to move away from passively listening and simply repeating back what they heard. With PBL, students are asked to think about the relevance of the subject they are currently learning. They apply that understanding by working with peers in an environment that models professionalism and by focusing on what the end product will look like.

The first step in creating a successful PBL environment is to create a culture of learning, engagement, and understanding. One essential element to that culture is motivation (Jensen, 1998); therefore, a teacher’s priority when planning should be to boost student motivation. To that end, PBL has the potential to inspire and/or spur students to be more proactive in their learning. For those already-motivated learners, PBL offers an opportunity to apply and demonstrate their understanding. For those students who have yet to find that enthusiasm for school, PBL may be just what they need to feel successful.

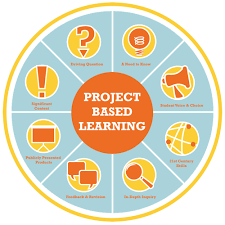

What is Project-Based Learning?

It is important to understand the components needed for a lesson to be considered project-based. Students are given a problem to solve that involves the following components:

- students’ thoughts, concerns, questions, opinions, etc. being heard and addressed;

- inquiry-based work;

- alignment with standards;

- emphasis on 21st century skills;

- reflection and revisions; and

- presentation of a final product.

The best place to start is with a problem to solve. This problem can originate from the teacher or from the students. Once students have invested time into brainstorming and researching the issue, the PBL unit continues with inquiry-based work. This work should require students to use 21st century skills that will prepare them for college, careers, and life. (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010)

It is important that reflection (i.e., self-assessment) and revision play a notable role in the PBL cycle. Students should receive feedback from their peers and from the teacher. Based on this feedback, they should revise their original work (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010). While time is often a limiting factor, students will benefit from multiple rounds of revisions. Additionally, rubrics will be helpful as the work becomes more complex.

The final step of a PBL unit is for the students to present their work publicly (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010). This can be done as individuals or in groups, but students often struggle with how to present in a professional manner. It may be helpful here to revisit the tenet of reflection and revision. Perhaps students do not excel when presenting their first PBL project, but feedback can help students achieve at presenting as they become more adept at working in a PBL culture.

What makes PBL different from other modes of instruction? It is the authentic nature of the work being done. Through PBL, students develop: (1) competencies that will transfer into a majority of fields, workplaces, research teams, universities, cultures, etc., (2) confidence, and (3) a temperament for learning. There is proximity between traits that are fostered in a PBL environment and those traits that lead to productive and fulfilling lives after high school.

How do you implement Project-Based Learning?

If the task of planning a PBL lesson containing all of the components seems overwhelming, it is okay to start with including one or two of them in a lesson before attempting PBL. For example, allow students the opportunity to share their opinion on the topic being studied. Another option is to scaffold the skills you expect students to need to fully participate in the PBL. In that same line of thought: plan, teach, and reflect upon an entire PBL unit before planning another. Students may provide helpful feedback that can influence the next PBL lesson.

As most teachers can attest, learning outcomes are not always immediately tangible. This remains true for PBL, which is why assessment should be thoroughly considered. One consideration is the use of rubrics, which may help make assessment less subjective. Other effective ways to gauge student learning gains are to assess based on their level of participation and on their written reflection.

There is a place in PBL for multiple-choice testing, essays, laboratory demonstrations, and even lecture. What matters is that the components of PBL are considered and implemented as completely as possible, and that students are being asked to challenge themselves and to take the risk that they may not learn the “answer” immediately.

References

Barrows, H. S. (1996). Problem‐based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New directions for teaching and learning, 1996(68), 3-12.

Jensen, E. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind.

Larmer, J., & Mergendoller, J. R. (2010). Seven essentials for project-based learning. Educational leadership, 68(1), 34-37.

Neville, A. J. (2009). Problem-based learning and medical education forty years on. Medical Principles and Practice, 18(1), 1-9.

Lindsay Lewis is an Instructional Coach with NC New Schools/Breakthrough Learning.